College of Science pigment researchers are using a rare mineral discovered in Norway more than a century ago as a road map for creating new yellows, oranges and reds that are vibrant, durable, non-toxic and inexpensive.

The new pigments also carry energy-saving potential: Their ability to reflect heat from the sun means that buildings and vehicles coated in them will require less air conditioning.

The study led by Mas Subramanian, who made color history in 2009 with the discovery of a vivid blue pigment now known commercially as YInMn Blue, was published in Chemistry of Materials.

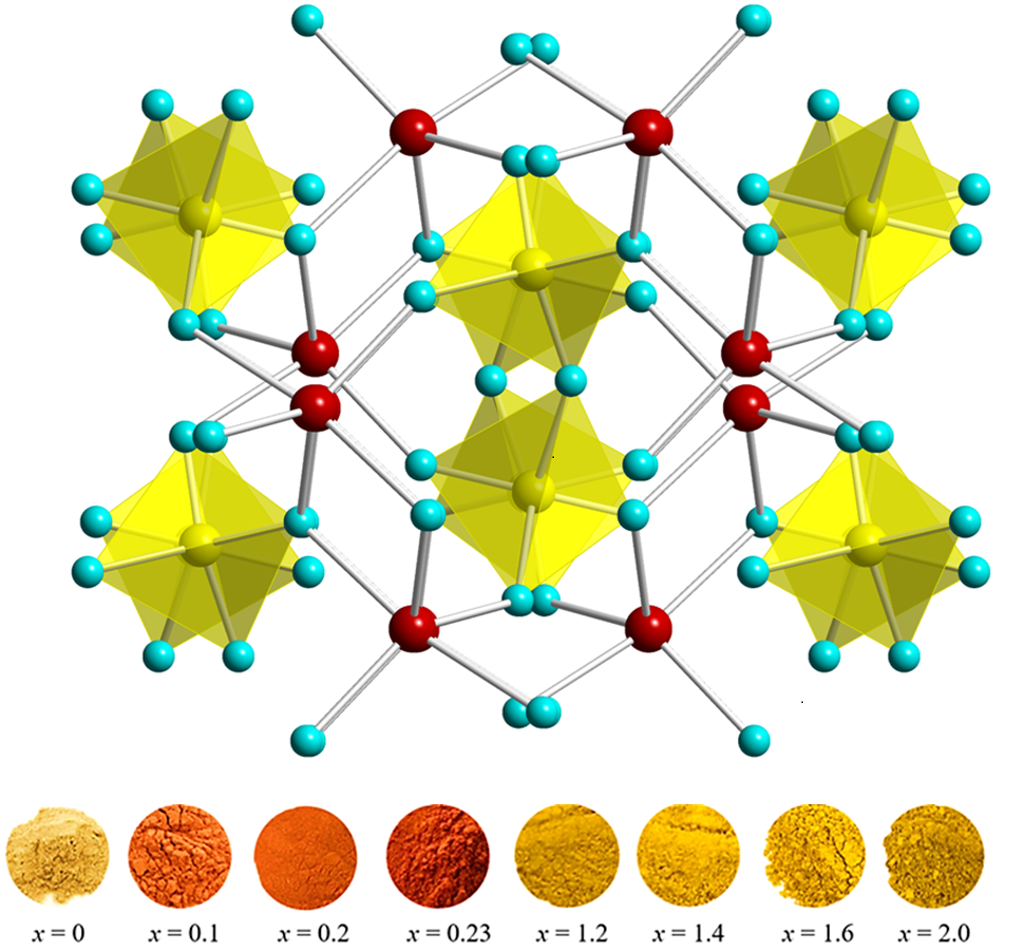

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the work centers around the crystal structure of thortveitite, a silicate containing scandium and yttrium. A silicate is any compound featuring silicon and oxygen.

Thortveitite isn’t known for vibrant colors, but by introducing the abundant elements nickel, zinc and vanadium into a thortveitite-like crystal lattice, scientists have produced a collection of intense yellow, orange and reddish pigments.

“The resulting color depends on the concentration and structural environment of divalent nickel, which is the primary chromophore responsible for the color,” said Subramanian, University Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Milton Harris Professor of Materials Science.

Chromophores are the parts of a molecule that determine color by reflecting some wavelengths of light while absorbing others.

“Although divalent nickel is known to produce yellow and green colors in inorganic compounds, it rarely produces oranges and/or reds,” Subramanian said. “The discovered pigments are stable under high temperatures and in acidic environments with no change in the structure or color properties, and they can be made in air at relatively low temperatures, around 750 degrees Celsius, which makes large-scale production feasible.”

Read more here.